Cloud Guts and Traffic

On the 27th, he loaded up the bike, climbed aboard, headed westward into Liechtenstein, and then fought the strongest headwind he had ever experienced to climb into Switzerland. This wind is known regionally as the “Fön” which, oddly enough, is the same word those crazy germans use for “blow-dryer.” Well, Our Legend in His Own Mind could hardly move his bike forward through the Blow-Dryer, and several sideward gusts nearly knocked him flat on his slowly-becoming-calloused ass. But he somehow made it over the hill, and the river, and through the woods, and on into Andermatt, where you can rest assured SOMEBODY’s grandmother has a house to which they go.

On the 27th, he loaded up the bike, climbed aboard, headed westward into Liechtenstein, and then fought the strongest headwind he had ever experienced to climb into Switzerland. This wind is known regionally as the “Fön” which, oddly enough, is the same word those crazy germans use for “blow-dryer.” Well, Our Legend in His Own Mind could hardly move his bike forward through the Blow-Dryer, and several sideward gusts nearly knocked him flat on his slowly-becoming-calloused ass. But he somehow made it over the hill, and the river, and through the woods, and on into Andermatt, where you can rest assured SOMEBODY’s grandmother has a house to which they go.

The loop he had chosen in central Switzerland turned out to be a lesson in frustration and frostbite. The day was a series of 3 extremely long, high climbs into freezing cold mist with zero visibility, fast, exhilarating descents requiring winter gloves and three layers of clothing, and short periods of moderate weather in between–during which he saw the sun for perhaps 45 minutes total during eight and a half hours of riding. Brrrrrrrrrrrr. One of the most beautiful locations in all the world, and he saw lots of . . . clouds. From the inside. The wet, dribbling, freezing cold, visibility-masking inside. Next time he sees Joni Mitchell, rest assured that Ours Truly is gonna ask her what the HELL she was thinking with all that “BOTH sides now” crap. “Joni,” he’ll say, “when you’ve taken a few good looks from INSIDE the *&#!^*@# clouds, get back in touch. Until then, why don’t you go play in some traffic?”

The loop he had chosen in central Switzerland turned out to be a lesson in frustration and frostbite. The day was a series of 3 extremely long, high climbs into freezing cold mist with zero visibility, fast, exhilarating descents requiring winter gloves and three layers of clothing, and short periods of moderate weather in between–during which he saw the sun for perhaps 45 minutes total during eight and a half hours of riding. Brrrrrrrrrrrr. One of the most beautiful locations in all the world, and he saw lots of . . . clouds. From the inside. The wet, dribbling, freezing cold, visibility-masking inside. Next time he sees Joni Mitchell, rest assured that Ours Truly is gonna ask her what the HELL she was thinking with all that “BOTH sides now” crap. “Joni,” he’ll say, “when you’ve taken a few good looks from INSIDE the *&#!^*@# clouds, get back in touch. Until then, why don’t you go play in some traffic?”

Of course, in Switzerland, on the 28th day of July in the Year of Our Lord 2003, one man took a look inside the clouds AND played in traffic. All at the same time.

Them Thar’s Thuh Alps, Pilgrum

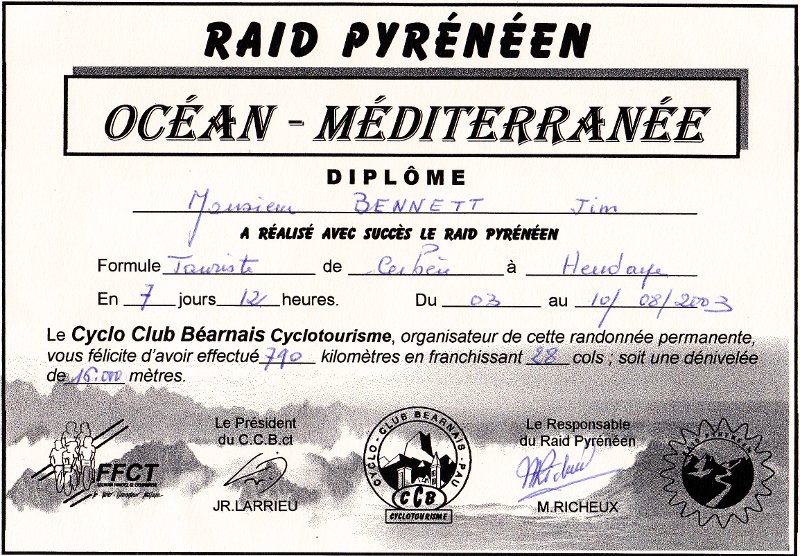

But enough about His Holiness. Let’s talk for a moment about the mountains themselves, and particularly about the high passes of the French Alps–those glorious ascents of the Tour de France. These are the true stars of the next phase of The King’s Juggernaut. Pedaling away from Grenoble on the morning of July 30th, his excitement palpably increased as the road signs began to show mileage (kilometerage?) to places like Bourg d’Oisans, L’Alpe d’Huez, Col du Galibier, Col de la Croix de Fer, and Col du Lautaret. No longer were these dream-like words sitting on the pages of Lonely Planet’s Cycling France. Nope. No longer were the images merely coming through a television set or jumping off the pages of newspapers and magazines. No way. They were all around him, drawing him onward. He reached Bourg d’Oisans around lunchtime, set up his tent, stowed his bags, and went to find the most famous climb of them all, L’Alpe d’Huez. Without betraying the tiniest outward hint of his fervor or resolve, Our Hero had decided that l’Alpe, aka “that sumbitch,” was goin’ DOWN. “L’Alpe,” he thought “is MINE!”

But enough about His Holiness. Let’s talk for a moment about the mountains themselves, and particularly about the high passes of the French Alps–those glorious ascents of the Tour de France. These are the true stars of the next phase of The King’s Juggernaut. Pedaling away from Grenoble on the morning of July 30th, his excitement palpably increased as the road signs began to show mileage (kilometerage?) to places like Bourg d’Oisans, L’Alpe d’Huez, Col du Galibier, Col de la Croix de Fer, and Col du Lautaret. No longer were these dream-like words sitting on the pages of Lonely Planet’s Cycling France. Nope. No longer were the images merely coming through a television set or jumping off the pages of newspapers and magazines. No way. They were all around him, drawing him onward. He reached Bourg d’Oisans around lunchtime, set up his tent, stowed his bags, and went to find the most famous climb of them all, L’Alpe d’Huez. Without betraying the tiniest outward hint of his fervor or resolve, Our Hero had decided that l’Alpe, aka “that sumbitch,” was goin’ DOWN. “L’Alpe,” he thought “is MINE!”

As it turns out, l’Alpe doesn’t belong to anyone. It belongs to the entire sport of cycling. L’Alpe is its Mecca, and the French Alps and the Pyrenees are its Holy Lands. The infamous climb to the top of l’Alpe d’Huez began within a mile of his campsite, and as soon as the road tipped upward he knew he was in a special place and that a wonderful experience was in store for him.

He was not to be disappointed.

The on-road graffiti so famous and familiar to anyone who has ever seen the Tour de France covered the pavement beneath his wheels: “Lance is God” and “Ullrich #1” and “VIRENQUE! VIRENQUE!” There were dozens, perhaps hundreds of his fellow cyclists on the mountain, heading up or heading down, or stalled on the side of the road, recovering. Every stripe of bicycle enthusiast under the sun was represented, from hardcore, in-training professionals to slovenly once-a-year Tour-o-philes who had dusted off their rusty mountain bikes to make–or attempt to make–the pilgrimage to the top of this iconic lump of rock. As for Ours Truly, he made it to the top in one hour and thirty-two minutes. Lance did it this year in 41 minutes, so there’s still some room for improvement on the part of Our Fearless Leader. But Lance had clearly better watch his back.

It was, to be sure, a fantastic, fantastic day.

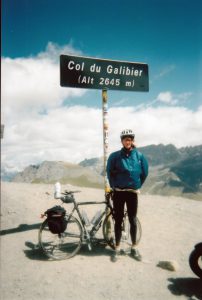

But it was the next day that was truly to stretch him to the very limits of his strength and resolve: 4 cols, 170 Kilometers, and–if you believe Cycling France–almost 13,000 meters of climbing. And all in one day (Cycling France divides the route into 4 full days, not including l’Alpe . . . but JB wasn’t interested in acquiescing to his mortality in this way. Nuh-uh. No-siree).

That loop (for a loop it was) was to take him to the tops of Col du Galibier (2654 Meters), Col du Telegraphe (1566M), Col du Lautaret (2057M), and Col de la Croix de Fer (2061M). The views he was unable to enjoy in Switzerland were presented to him on this day in spades. The view from Galibier (the highest altitude of his entire trip) was unparalleled. As was the windspeed. The descents from Galibier, Telegraphe, and la Croix were truly incredible–smooth and dangerously fast . . . not to mention the sheer, intimidating drop-offs awaiting anyone careless enough to miss a turn. There was a very low point early in the afternoon, as he travelled through a butt-ugly industrial butt-ugly valley joining the base of Telegraphe to the beginning of the (28km!) climb up Ye Olde Iron Cross (Croix de Fer). According to his map, he was to have a nice, gradual and restful descent for about 30 butt-ugly kilometers as he approached butt-ugly St. Jean de Maurienne and the start of his not-remotely-butt-ugly climb. He had actually looked forward to this reprieve the entire first half of the day. MADE PLANS around it, even. Pah! What ACTUALLY happened was that the wind was being funnelled through this butt-ugly valley of butt-ugliness directly into his face with such force that on several occasions he had to pedal in order to get his bike to move DOWNHILL.

That loop (for a loop it was) was to take him to the tops of Col du Galibier (2654 Meters), Col du Telegraphe (1566M), Col du Lautaret (2057M), and Col de la Croix de Fer (2061M). The views he was unable to enjoy in Switzerland were presented to him on this day in spades. The view from Galibier (the highest altitude of his entire trip) was unparalleled. As was the windspeed. The descents from Galibier, Telegraphe, and la Croix were truly incredible–smooth and dangerously fast . . . not to mention the sheer, intimidating drop-offs awaiting anyone careless enough to miss a turn. There was a very low point early in the afternoon, as he travelled through a butt-ugly industrial butt-ugly valley joining the base of Telegraphe to the beginning of the (28km!) climb up Ye Olde Iron Cross (Croix de Fer). According to his map, he was to have a nice, gradual and restful descent for about 30 butt-ugly kilometers as he approached butt-ugly St. Jean de Maurienne and the start of his not-remotely-butt-ugly climb. He had actually looked forward to this reprieve the entire first half of the day. MADE PLANS around it, even. Pah! What ACTUALLY happened was that the wind was being funnelled through this butt-ugly valley of butt-ugliness directly into his face with such force that on several occasions he had to pedal in order to get his bike to move DOWNHILL.

I leave you, dear friend, to think about that for a minute.

[insert one minute pause here]

In any case, he arrived home at the end of his strength, ate two dinners (something that happened pretty often during his 4000-6000 Calorie-per-day adventures), and tumbled into bed, dreaming of flat roads, tail winds, and an unchapped ass.

The Last Train To Dorksville

For a country so enamored with All Things Bicycle, it can be remarkably difficult to get one’s bike from place to place using French railways. Our Enervated Friend was told flatly that there was “no way” to get his bike from Grenoble to Cerbere by train. “Impossible!” Being one of the most annoying guys on the planet has its benefits, however, and he was soon on his way to the Mediterranean coast WITH his bike, albeit with about 6 connections and lots of layovers before him. The only other notable event this day is recorded thusly in his daily journal:

Please repeat after me, slowly:

The Transglobaliste [“The Transglobaliste“] is a dumbass [“is a dumbass”]

Once more:

The Transglobaliste [“TheTransglobaliste“] is a dumbass [“is a dumbass”]

OK…

Now, the reason for this is The King got off of the last train one stop too soon, and had to ride 10km at top speed in order to reach (not to mention FIND) the correct train station and catch a connection to Avignon. He made it with just enough time to find the correct track, haul his rig down and up some stairs, buy a coke, and jump on the train–which, by the way, was literally pulling into the station. Just like in the movies.

On the bright side, he tells me that it did help pass the time.

Arriving in Cerbere shortly after 10pm, he found a campsite about 3km north of town, just off the glorious Mediterranean, and settled in for a couple days’ rest and recuperation.