Coastal China (2016)

Coastal China (2016)

WHERE : Yueqing, Liushi, & Beijing

WHEN : October-November 2016

OBJECTIVE : Return to China after 20 Years

DISTANCE : NA

CLASSIFICATION : Walks, Words (Work!)

Through the Looking Glass

Twenty years ago I glimpsed the developing world for the first time. During a stint in pre-handoff Hong Kong for toy-related software brainstorming, an associate arranged a nine-day, three-stop side trip to the post-Tiananmen Square mainland—Xian, Beijing, and Shanghai. This was a few years after the iconic rebellion’s suppression; certain topics could quickly derail a conversation, turning interlocutors hushed and nervous. The country’s inner workings were opaque to outsiders, the airwaves full of bright red- and yellow-hued propaganda, the borders largely impermeable in both directions. To my inexperienced eyes, there was a ponderous, monolithic air of authoritarian rule.

The two most visible signs of things to come were those obscene Golden Arches—China’s first McDonald’s—and a large, menacing clock on the National Museum’s façade in Tiananmen Square—giant red LED digits on a black background, counting down the seconds until the People’s Republic reclaimed Hong Kong.

*****

Fast-forward to this June (2016). With a shiny new visa in my passport and the sketchiest of plans I booked a two-month layover in China, en route to the US for the holiday season. Four months in advance. I intended to sort it out when I arrived in Beijing in October. In between came rural Nepal, the Indian Himalayas, and Varanasi, providing lots of planning time. Yeah. No. Months later I arrived unprepared at PEK baggage claim, exhausted, ill, and unsure of how to proceed. I had the vaguest of plans to immerse myself in Mandarin for at least a month, and perhaps teach a bit of English, but where?

It was challenging. China is less forgiving of seat-of-the-pants travelers than some other places for two simple reasons: the language (particularly written) and the infamous Great Firewall. Google Maps? Google Translate? Forget it. Wanna use the Chinese version of Uber? Tough luck. There are local analogs to all of these things, but whereas most places on earth provide some Romanized alternative, not so China. It’s logograms or nothin’.

And yet I managed. Five days in the capital got me a local SIM card, a VPN to bypass the Great Firewall, and a place to stay, gratis, in far-away Zhejiang Province—China’s coastal southeast. I boarded a bullet train bound for Wenzhou. Nine hours and sixteen-hundred kilometers later my China experience began in earnest.

I spent the next seven weeks in and around a small city named Yueqing, befriended by photographers, teachers, policemen, government officials, numerous shopkeepers, a village drunk, and a gaggle of students. I climbed in the lovely Yangdang Mountains, forded the scenic Nanxi River, ingested frightening quantities of sea-flora and -fauna. I learned scant Mandarin, but became a chopstick maestro. I taught English. Unexpectedly, and to my happy surprise, I found the peace of mind to complete the new and improved Transglobalist.com.

*****

A few ex post facto observations about the new China: McDonald’s is now everywhere, though KFC is the undisputed champion. People speak openly and frequently and articulately and passionately for and against their government and military, including His Holiness Chairman Mao—they are, in every meaningful respect, as free as, or freer than, their American counterparts. The average Chinese knows far more about the vagaries of US geography, government, and politics than the average Yank knows of China’s. It’s an expensive country, but no one who considers you a guest will let you pay for anything (and I mean anything).

And with that, I’m off to eat a spicy fish head, drink some rice wine, sing a bit of karaoke (80’s Power Ballads, thankyewverymuch), and charge my electric bicycle so I can repeat the whole process tomorrow.

Live long and prosper & Gom Bei (aka Bottoms Up),

—jim

December 05, 2016

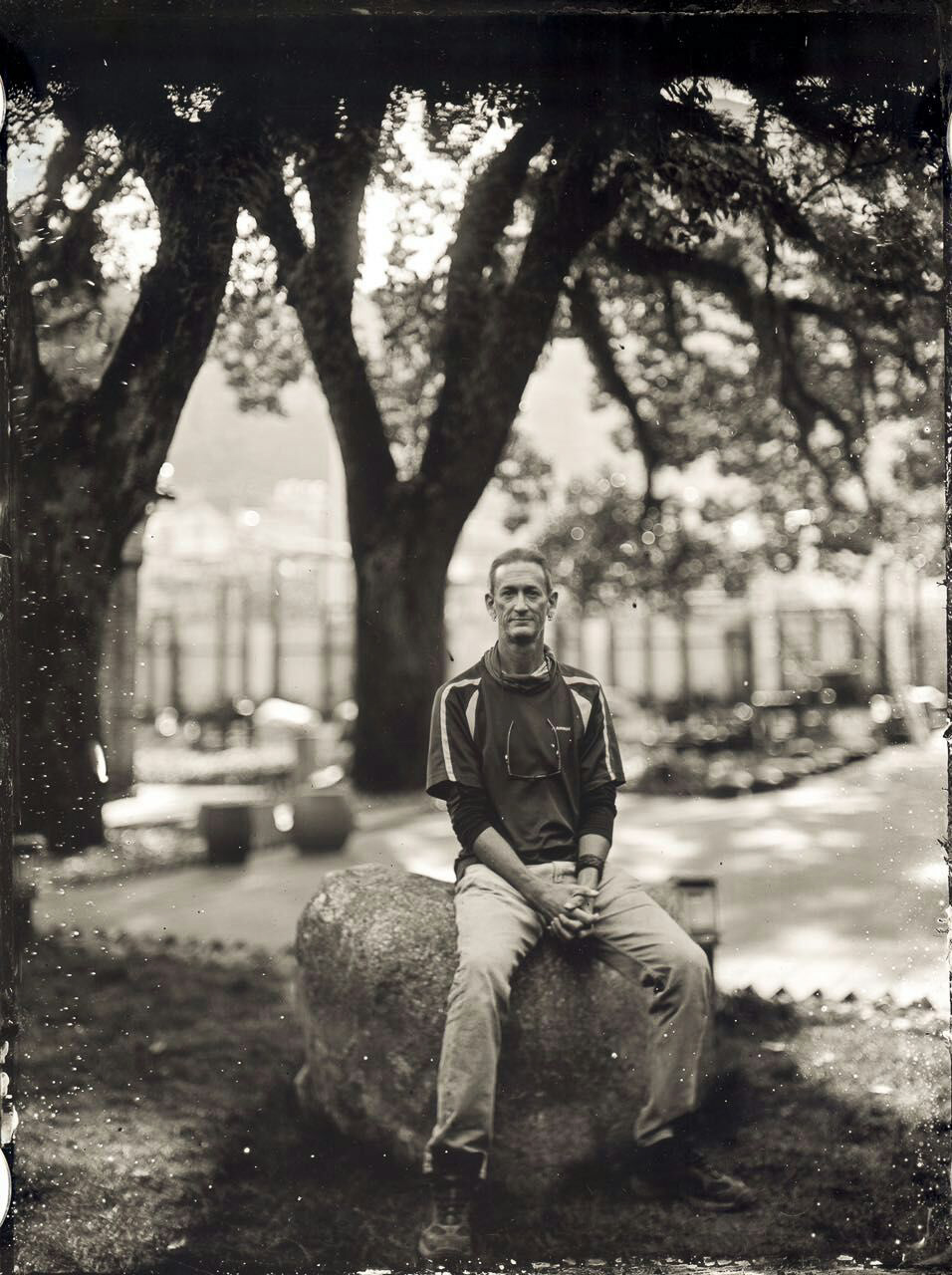

A standout experience of my stay in Yueqing was meeting eminent photographer Zhao Hui Ye–an expert in wet plate photography, aka the collodion process. This is a 150-year old technology whereby the image is recorded directly onto chemically treated glass. As the linked Wikipedia article states, and as I can attest firsthand, this style of photography “requires the photographic material to be coated, sensitized, exposed and developed within the span of about fifteen minutes.” But what a fantastic result!

Early in my stay I was fortunate enough to stumble upon a wonderful artists’ hangout–a coffeeshop called Moss Coffee–as one of my friends was shuttling me from site to site, trying to show off his village. I became friends with the shop’s owner–the delightful Feiqing–who introduced me to many local artists, musicians, and photographers, all of whom were regulars in her establishment.

My thanks to Feiqing and all the folks at Moss Coffee (also, for what it’s worth, the espresso is damned good!), I hope to see you all again soon.

Images from the Road

Posts from the Road